From Video Signals to Bytes: Preserving the Legacy of CS at CMU

Tuesday, January 12, 2021 - by Cristina Rouvalis

The image from the videotape is blurry, deteriorated from the passage of time, but the professor is razor-sharp as he talks about the future. Herb Simon stands in front of a class at Carnegie Mellon University, musing about the difference between artificial and natural intelligence.

"So I suppose there are some respects in which it makes a difference whether we're talking about artificial or natural intelligence. When I'm in an airplane during a bad rainstorm, I always wonder which I'm being landed by," says Simon. The class laughs, and Simon, bespectacled and wearing a suit and tie, lets out a wry smile.

This is Herb Simon in September of 1971, before he won the Turing Award. Before he won the Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences. Before he was widely heralded as a pioneer in artificial intelligence.

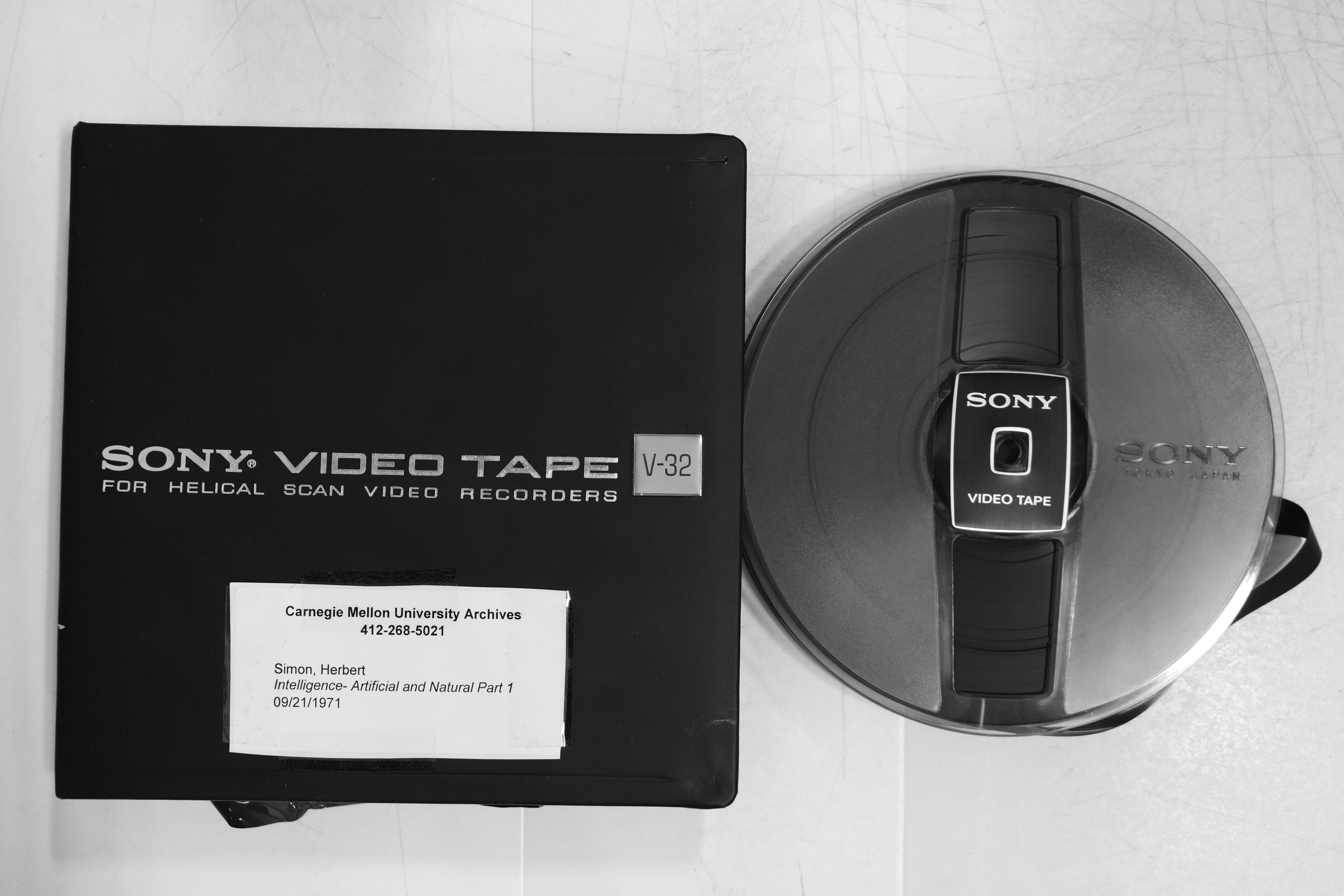

Thanks to the University Archives' renewed investment in audiovisual preservation, the public can watch a digital recording of that magical moment, one of many recorded at CMU between 1970 and 1993. Some 400 videotapes make up the Computer Science Videotape Collection, which captures the early, heady days of the field when a group of visionaries converged on a depressed steel town and through their research and collaboration, defined the very essence of modern life. These historic documents exude the sense of excitement and infinite possibilities during the formative years of the Computer Science Department and document the profound role of the School of Computer Science in defining the field.

To date, archivists have digitized 30 tapes, including recordings of Allen Newell, Raj Reddy, Alan Perlis and other SCS pioneers. A portion of these can be viewed on the University Archives' Vimeo Channel.Other tapes highlight speakers and thought leaders from around the world who came to CMU to lecture or serve as visiting professors. Another 20 videos have been slated to be digitized by Preservation Technologies, a Cranberry Township-based company. But the process is expensive, leaving approximately 350 videos vulnerable to deterioration. Each hour-long tape costs about $250 to digitize, and the archivists hope to complete the project of digitizing them within the next three to four years.

"It's really important that we do this as soon as possible, before they degrade even further or it becomes too cost prohibitive," said Emily Davis, archivist at Carnegie Mellon. "Some of the tapes are so fragile and unstable. Some have mold that can eat away information on the tape."

One of the videotapes captures Allen Newell, a Turing award winner in 1975, giving his famous "Desires and Diversions" lecture about dealing with the distraction of life while still pursuing his passion for research. In the question-and-answer segment, Newell commands the classroom, speaking with remarkable dynamism and animation.

"I learned what a fabulous teacher Allen Newell was," said Katherine Barbera, archivist and oral historian at Carnegie Mellon. "He had this wonderful personality and a good sense of humor."

In another video, Mary Shaw, then a young Ph.D. student, introduces a lecture by Alan Perlis, the first winner of the Turing award in 1966 and head of the Computer Science Department. Shaw would go on to become a legend in her own right as founder of the Software Engineering Institute and now the A.J. Perlis Professor of Computer Science.

"These tapes bring history to life for current and future generations in a way that other archival materials, notes, letters, emails, code and even photographs simply can't," Barbera said. "The tapes really help the students grasp the legacy that they're inheriting."

Leaders within the Computer Science Department, established in 1965, understood then the importance of documenting the innovative ideas contained within their lectures. They had the foresight not only to realize how far out in front of the field they stood, but also to preserve CMU's role as visionaries in the emerging field as it was being formed. These videos are a treasure trove, which cement SCS's foundational legacy, allowing current and future generations to experience this history as it was being made.

Making Films About Computers and Using Computers To Make Films

Raj Reddy stands before an audience holding up a new Bally video game console. It's October 1978, and in a few months the game will become a popular Christmas gift.

"Basically you can play all kinds of games. You can even do basic programming with it," he says. "So what I thought we would do today is just generally raise questions about how these are built and why they are built that way, and why they are so inexpensive. This is about $50," says Reddy, who would go on to found CMU's Institute for Software Research and become dean of SCS.

Reddy wanted to take the documentation a step further and produce 16 mm instructional films about scientific concepts to help him secure grant funding for research, just as he had while he was a professor at Stanford University. In the process, he helped launch the career of one of the pioneers of computer animation.

Ralph Guggenheim (DC 1974, MCS 1978) arrived at Carnegie Mellon in 1969 as a liberal arts major. But Guggenheim really wanted to be a filmmaker. After reading about the emerging field of computer animation, he decided to design his own master's degree in the Computer Science Department, specializing in computer graphics and filmmaking. Raj Reddy was his advisor and mentor.

One day, the student went on a walk with Reddy, who told him about his idea to produce promotional films on research subjects such as voice recognition. "Looking back," Guggenheim said, "it was sort of like that closing scene in Casablanca — the beginning of a beautiful relationship."

Six months after graduation, while working at the New York Institute of Technology, Guggenheim received a phone call from Los Angeles about a job opportunity at Lucasfilm. The company had called Stanford, who recommended Reddy, who recommended his former student for the job. Several years later, Lucasfilm split off to form Pixar, with Guggenheim as co-founder and vice president. He produced the first feature-length computer animated movie, Toy Story.

"I wouldn't have done Toy Story without Raj Reddy," he said.

Today, Guggenheim wants to help preserve the thrilling history he lived through by helping to support the preservation of the Computer Science Videotape Collection.

"These videos [in the Computer Science Videotape Collection] represent more than just the dry research results. They represent the flesh and blood of the people who did the work, the camaraderie and the collegiality in what they were doing," Guggenheim said.

The Protectors of the Archives

For years, these videos multiplied by the dozens, while Catherine Copetas, the assistant dean for Industrial Relations, collected them. Without Copetas, the collection may have perished. She stored stacks on the shelves of her office in Wean Hall. The overflow tapes piled high in her storage closet. "The hoarding jokes were getting old," she quipped.

One day during winter break in the early 2000s, some of that history nearly washed away. A graduate student in the office above Copetas had left the window open, the pipes by the window froze and water flooded the office. Ceiling tiles came crashing down, the water soaking the walls. Luckily, the videotapes that were being stored there survived thanks to the quick work of two computer science professors — Dana Scott and Howard Wactlar — who rushed to salvage what they could from her office.

When the school moved to the Gates Hillman Center in 2009, some of the videotapes were scattered in storage rooms in Gates Hillman and Wean Hall, with the overflow to a storage unit on Penn Avenue.

For years, the videos were "missing in plain sight," as Copetas puts it. "Playing the oldest ones wasn't possible. Technology shifted, original equipment broke and it was dangerous to even try to view for fear of destroying them." Even when it was nearly impossible to find a reliable player to view the old tapes, Copetas knew they were worth a cluttered office and storage closet.

"In my heart, I always knew they had to be saved," she said. Then in 2017, Copetas met Barbera and Davis, who expressed interest in the collection. "I knew the tapes had found a good home in the University Archives and that the history contained in them would be restored." The videotapes she guarded form part of the history of both the university and the city. "Why CMU? Why Pittsburgh?" she said. "Why would this city become an intellectual powerhouse?"

"It's magical to get all these people here," she said. "When you have magic, you don't waste it."

The Power of Pioneers: Saving a Legacy

In June, some 150 alumni from around the country tuned into Zoom to watch short clips of Newell, Simon and Reddy, as well as a brief presentation by Guggenheim who reflected back on the trajectory of his career. Others watched after a recording of the "The Power of Pioneers: Preserving CMU's CS video collection" was posted online.

Archivists also invited alumni to get in touch and share their personal stories of learning or working with these pioneers. One alumna inquired about the female computer scientists in the archives, and Emily Davis sent her a list of women and the dates they had given lectures.

"Everyone has been so excited," Davis said.

"A lot of alumni are saying, 'I was there. I was in that lecture.' "

For more information on the project or to watch the recording of the webinar, visit the archived online event from June. You can also make a donation to help preserve the Computer Science Videotape Collection fund.

For more information, Contact:

Kevin O'Connell | 412-268-2064 | kevinoco@cs.cmu.edu